A

Note on Traditional Farming in Ireland

By Margaret Lloyd

This past summer, I spent 3 months

rambling round the Irish countryside. By matter

of chance and good research, I found a gem of a

man, Bernie Winters, who lives on the west side

of Clare Island where he farms the way his father,

grandfather and 4 previous generations have farmed.

Both literature and other farmers have told me that

Bernie’s ways are typical, not of just Clare

Island, but of the west coast in general and, in

particular, any farm close to the ocean. While others

on the island weave tidbits of the ways their fathers

taught them into their conventional methods, Bernie

is definitely the only one on Clare Island, and

perhaps on all the west coast, still farming entirely

by the traditional methods. He rears 80 sheep, 2

cows (1 for milking), 13 hens, and a dog named Pinch.

A Bit of Clare Island’s

and Bernie’s History

Clare Island is a small island,

roughly 3 miles square, but among the largest of

this "365"-island archipelago of Clew

Bay, northwest Ireland. By the mid-1700s, the British

ruled the Irish parliament as well as their fields.

In 1790, over the course of 11 months, the boundary

wall that circumnavigates the center area of Clare

Island was erected. As seen by the excessive quantity

of stones that naturally overpopulate the Irish

fields, building walls was an obvious practicality

to farm the countryside. And from the number of

walls that define today’s picturesque landscape,

one can see that building stone walls was a favorite

pastime for the British in Ireland. And so the walls

stand in memory of an enslaved heritage, but they

have also been greatly appreciated and utilized

by millions of people since.

On Clare Island, this wall created a commonage where

sheep and cows were allowed to graze. "Units"

of the commonage were divvied out to the islanders

depending on their wealth and collectively used

for the island's sheep, cows and donkeys. For example:

6 sheep = 1 cow = 1 unit = 1 acre on the commonage.

Bernie’s family was given 50 units, which

he still owns and where he keeps a portion of his

sheep. With a wall, a full-time ‘herder’

was no longer necessary, and crop loss to animal

grazing became an obsolete worry. The wall was seen

as an improvement to the community because previous

to that, the animals roamed the island freely, making

no distinction between the wild and cultivated fields.

However during the famine, the island lost nearly

its entire population and has never restored its

former 900 inhabitants, but remains at a mere 140,

on a good day. And so the commonage has taken on

a new meaning ,and grazing one’s sheep and

cattle there is seen as vital to keeping the grasslands

"mowed" and fertilized.

In this century, a few significant changes of home

and farm life have occurred that make Bernie’s

way of life slightly different from his ancestors’,

as well as slightly easier. In 1912, Bernie’s

grandfather received a grant from the government

to put slate on their cottage’s roof to replace

the thatch. Bernie’s family never vaccinated

the animals, and they would lose half the flock

each year. Now that Bernie vaccinates his animals,

he only loses the odd one. This resulted in a huge

improvement in the quality of life that the sheep

live, the wear that the land bears, and the labor

and time that the farmers contribute. In 1983, Bernie’s

father installed electricity in the house, which

Bernie uses for a light bulb in the cottage and

one in the barn, a radio to listen to Irish radio1,

and small television to watch Gaelic football. Growing

up, Bernie always cooked over an open fire; however,

80% of the heat produced was lost, and so Bernie

bought a stove in the mid-1980s to more efficiently

burn the turf that he collects. And now, Bernie

receives subsidies for each head of sheep and cattle

he raises.

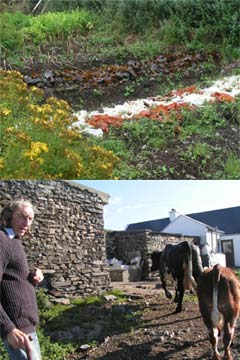

Bernie Winters is a tall man,

perhaps in his late 70s, living in his Irish cottage

on the sea. Made of stone, lime plaster, and the

hands of his 17th-century ancestors, this cottage

has reared 7 generations of Winters. Continuing

on the land where his family first began, Bernie

stewards that land the way they taught him, and

that’s where he showed me the ways.

On my first day we went to the

secret garden that is not hidden from the neighbors,

but rather from the gales. Billowing with force

year-round and particularly in the winter, the gales

arrive having been unobstructed by any landmass

for thousands of miles, pounding their spirits onto

the shores of western Ireland, against the stone

cottages and across Bernie’s garden. Standing

against this assault, thick hedgerows of fuchsia

and thicket are grown 9 ft tall to surround the

500-sq-ft rectangular garden containing his "lazy

beds," as Bernie calls them. They are about

4 ft wide and 15 ft long, growing onions, carrots,

beets, lettuce, potatoes, parsnips, and many herbs

including St. John’s wort, fennel, thyme,

rosemary, parsley, borage and ginger-mint. It is

only during the spring and summer that he plants

these beds, for the weather is too wet the rest

of the year for the trouble of growing. Furthermore,

it is during this time that the beds are put to

rest and given time to "replenish."

As soon as the winter rains break,

Bernie breaks the land for the first of the spring

plantings. Onions, garlic and lettuce are sown between

the 1st and 13th of March, depending on the weather.

The February frosts have always been welcome help

since they do the initial backbreaking work of cracking

and opening up the compacted winter soil. However,

in recent years, frost has been a missing tool all

across Ireland. Following the vegetable plantings,

the ubiquitous and essential spud is planted under

the spring’s new moon or on Good Friday. The

main crop is Kerr’s Pink and Cára,

while the early crop is the British Queens. In each

row, the spuds are sown 18 in apart while the rows

are laid 12 in apart. Later in the spring, carrots

are sown. Bernie says the best time to sow them

is in the middle of May.

In the late summer, changing ocean

and climatic patterns begin depositing seaweed on

the shores. One kind in particular has for centuries

been of utmost value to the farmers of western Ireland.

For several mornings, we collected the slimy bundles,

full of potash, to spread on the beds after harvesting

the spring potatoes. All the potatoes are dug out

except those which he selects for seed and leaves

in the beds until October when they are dug up,

stored until December, sprouted in the house and

planted in March and April. On those freshly forked

beds, a single layer of freshly collected seaweed

is laid and left to decay. After a month, we repeat

the process. If there is enough seaweed on the shores

for a third layer, he will collect it, but otherwise,

two is plenty. But that is not it for fertilization.

After the seaweed has rotted, the weather, too,

has turned rotten, and so the two heifers and Tom,

the donkey, are brought into the barn to live for

the winter. Their dung is collected and put on the

beds where it can rot in the rains until spring

planting. This is the centuries-old technique of

Irish fertilization.

1. The only remaining station

in Ireland that broadcasts solely in Irish, delivering

traditional music and the latest news.

2. Unique to Ireland, a cross

between soccer and rugby.

On the other side of the boithrin3 lie seaside hills

with steep cliffs, where Bernie mimics a similar

routine. Here, he has two large fields growing oats

and potatoes that are alternated each year. Only

one layer of seaweed is applied there, and ten loads

of manure are added to each ridge. Each ridge is

4-5 ft wide and 200 ft long. To Bernie, one load

is comprised of two wooden cleaves attached to the

side of Tom, filled with manure. My rough estimate

is that three five-gallon buckets fit into a cleave.

These cleaves were made by Bernie from driftwood.

Last year, he did a little experiment. Since the

sheep pastures are not cared for in any intentional

manner, their care is simply that the sheep graze,

the rain waters, and their manure fertilizes. In

a small patch, Bernie laid one layer of seaweed

last summer to rot in the weather, just as he does

in the beds. We paid a visit to that spot in August,

and the lushness, depth of color and diversity of

greens it supported were starkly richer than the

surrounding pasture. Seaweed's ability to fertilize

the land and encourage beneficial growth was clear.

It was not only potato-harvesting and seaweed-collecting

season, but also oat-cutting season. We sharpened

the sickle and set out to the fields. Bernie had

already cut half of the field during the first two

weeks of August. And so, we had the second half

to cut. To use the sickle, with a crescent loop

movement, the blade carves the section to be cut,

and the alternate hand takes the oats in a bunch

to push them in the opposite direction that the

blade then cuts through. When a large handful is

collected, it's then laid down in bundles forming

an orderly pattern of freshly cut oats that begins

to tag behind Bernie. The next row is then laid

down in a similar way; however, the oat rows are

always cut in pairs so that the oats laid always

have their grain heads facing, and even resting

on, each other. Each of these bundles makes up a

sheaf that is then tied together by gathering 4-5

stalks to wrap and twist-tie it secure. The next

step is building the conical stooks for drying.

Each one contains 20 sheaves, with 16 arranged in

a spiral and 4 upside down on top to cap it.

3. Irish for a small lane.

No Irish farming teaching is complete

unless it is done in the rain. The night before

we started up cutting the oats again, it was spilling

rain and howling wind. It did not hold back from

another bout in the early morning, and so we spent

some time watching the rain, cracking jokes and

drinking tea, waiting for it to pass and then giving

the oats an hour to wick off the heavy water. Then

we were off for the day's work; it spit a little,

but we didn't mind. We took lunch for a half-hour

while it poured rain and then kindly held back.

Consequently, we held off for an extra half-hour

and then went back to the sickle. We made good progress

and got into a rhythm under the thick cloud cover,

fresh air and sweet smell of wet grains. We persisted

through the spits again; however, this time they

got progressively harder. At that point, we each

took to a stook and ducked beside its sturdy build,

hoping for some “cap” protection as

well. Behind me, and to both sides, stooks of oats

kept us company, and in front of us, the uncut grains

stood up against the weather. After that heavier

bout of wet weather, we refrained from cutting more

and simply “stooked” the remaining sheaves,

wet as they were, into the inherently gorgeous stooks.

The field was finished the next day with a few hours

work.

Margaret Lloyd worked as an apprentice

and assistant to the garden manager at Ecology Action

for two years and has now taken to the “fields.”

At the end of October, she will be going to Guinea

with OIC International to assist in establishing

Biointensive gardens around family homes and in

communities. She teaches backyard Biointensive gardening

in Palo Alto and takes time to travel while teaching

sustainabili along the way. |